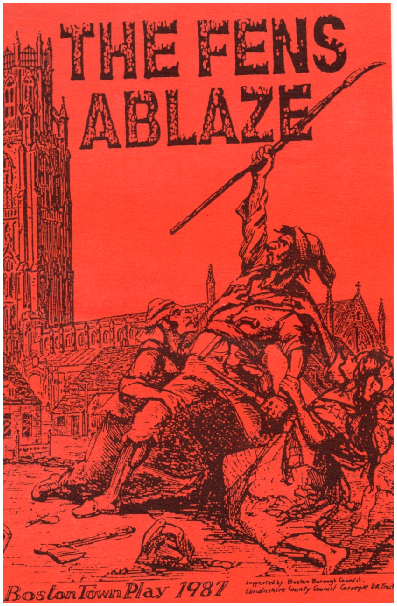

The Fens Ablaze as reviewed by Andy Barrett on his website https://communitytheatreplaywright.wordpress.com/

It’s funny how suddenly out of the blue someone gets in touch and wants to talk about a production that you did nearly thirty years ago. But that’s what happened recently when Andy Barrett, a Nottingham based playwright and doctoral researcher who is doing some work on the texts of community play, got in touch and asked for a copy of the script of THE FENS ABLAZE. Here’s what he wrote on his blog.

I ’ve just finished reading two community play scripts – The Fens Ablaze by Doc Watson

(Boston, 1987) and the Dreaming Pond by Peter Spafford (Upton cum Kexby 1990). The

first is a rabble rousing piece that in its introduction draws attention to the links

between its subject matter – the fen riots of the 1770’s that were caused by the

enclosure acts – and ‘echos (sic) in Britain today’. The second is a very atmospheric

and beautifully constructed dream play that has at its heart (and told through a

story within a story within a story) a plot that is connected to a time, like Watson’s,

of social turmoil; here the English Civil War. There are many similarities between

them; not least the battle for and the appropriation of common land.

’ve just finished reading two community play scripts – The Fens Ablaze by Doc Watson

(Boston, 1987) and the Dreaming Pond by Peter Spafford (Upton cum Kexby 1990). The

first is a rabble rousing piece that in its introduction draws attention to the links

between its subject matter – the fen riots of the 1770’s that were caused by the

enclosure acts – and ‘echos (sic) in Britain today’. The second is a very atmospheric

and beautifully constructed dream play that has at its heart (and told through a

story within a story within a story) a plot that is connected to a time, like Watson’s,

of social turmoil; here the English Civil War. There are many similarities between

them; not least the battle for and the appropriation of common land.

But for now I want to focus on the outsider. In Ann Jellicoe’s book ‘Community Plays and How To Put Them On’ she says ‘Organise your villains so that if possible they come from out of town: people whom the community can comfortably unite against’. The impact of the outsider is obviously a potent force in many plays and stories, in fact as Stephen Lowe suggests (in David Edgar’s ‘How Plays Work’) ‘all plays are about people escaping or invading secure communities’.

In both of the plays that I have just read the communities are not secure; they are in flux. In each the outsider serves a different function, both of which offer interesting perspectives on the potency and function of this role within the writing of community theatre.‘The Fens Ablaze’ by Doc Watson begins with a number of outsiders. First of all the Grand Sluice Fair, which opens the performance in typical community play fashion, is interrupted by a Visitor calling out ‘Call that a Sluice, sir! That’s nobbut a few planks o’ poor wood strung across yer river’.

The fair is then interrupted further by a Puppet Master who has a play for us ‘fresh from London’, a play that features ‘a large fat caricature of King George III’. This grotesque attack on Royalty begins but is curtailed when Eden Simpson grabs the puppet King and tells the Puppet Master that this play is not wanted here; however well it’s done in London – ‘That’s London, this is Boston’. ‘Boston, Boston, Boston’, taunts the Visitor, ‘Thou hast naught to boast on / But a grand sluice and a High Steeple / A proud conceited ignorant people’.

The first job of the outsider is set up very clearly here. If there is an outsider there must be an insider. And this antagonising work of the Visitor, by specifically attacking the connection to the place in which the performance is sited and the audience lives, creates a strong bond between the ‘them’ of the play world, and the ‘us’, the audience, of the performance world. It’s an easy trick – witness any pantomime where the villain will assail the shortcomings of the location in which it is taking place – but it is also a very effective and highly useful one.

Following the Sluice Fair we begin to meet a number of characters all of whom gravitate around what will be the main issue of the play – the enclosure of the Holland Fen which is due to take place. Mrs Wyche makes sure that we realise that ‘This is an important day for our town’, whilst the fact that such an event will lead to winners and losers is made clear as William Smith replies ‘If this bill for Enclosure gets passed – fat riches for us all, eh, Mrs Wyche?’ Richard Kitchen may ask ‘what of the poor folks on that Common Land?’ but for Smith, once the sluice that is being opened does its job and drains the land, this ‘pack of ignorant mud jumpers must move elsewhere’.

Smith, we learn, is not a man who we should feel any sympathy for, swiftly revealed

as a heavy drinker, a gambler and a misogynist who has ‘creditors baying at my heels,

I need this Enclosure land’. And when Smith is informed that Mr. Charles Anderson

Pelham is calling in the mortgage on his house in Swineshead (Hardwick Hall), and

is planning to take land (Pel hams Plot) from Smith in lieu of his unpaid mortgage

bills, we understand that he is a character who will be vulnerable to temptation.

hams Plot) from Smith in lieu of his unpaid mortgage

bills, we understand that he is a character who will be vulnerable to temptation.

Away from the world of the fair are the slodgers, the fen people, represented by the Loynham family who on hearing about the proposed drainage do not seem overly concerned with the implications: ‘the fen folk exist above and beyond the law, there is simply no connection between the two … We’ve bin here fer more years than there’s numbers’. And when, in a later scene, Norris Loynham is told that come Spring the Common Land is to be fenced and that Norris will end up having to work for a living like everyone else, Norris simply refuses to believe this – ‘Nobbody’ll stop me catchin’ a pike or shootin a widgeon when Oi loikes’.

The play then has a series of locals, a series of people who are the insiders and yet are also distinct social groups that are in conflict with each other. We understand and expect this conflict to break out, and that the play will be an examination of this, but – adhering to Jellicoe’s proposition that the villain needs to be an outsider, presumably to assuage the representation of conflict from within a community – another outsider is now to appear; this time with much more devastating consequences.

This outsider is called The Stranger and he makes his entrance once the positions around the issue of the enclosure of the Holland Fen have crystalised. There is opposition from the genteel liberal character Mrs Wyche; there is opposition from the radical Robert Chapman; there is opposition from the toft holders who do not appear to be having any say in what is taking place; there is opposition from the slodgers; there is opposition from the butchers and graziers who have been informed by the Corporation that they will now need a permit to trade in the market. Trouble appears to be brewing.

The Stranger approaches William Smith. He has managed to get hold of Smith’s mortgages

and offers him a hundred gold sovereigns if he will help him: ‘there’s goin’ to be

trouble, Mr Smith – Enclosure trouble – we see it before, we’ll see it again; it

draws trouble-

At the meeting Norris Loynham declares that it’s the Act of Parliament that needs to be defeated, not through parliamentary action but by actually destroying the paper on which it is written – ‘The Act. That’s the evil thing. If we destroy that, then we destroy all their claims’. The first act ends as the mob, roused into action and ready to attack Boston, goes to the house of Edward Draper, the clerk to the commissioners. As the act is handed over and torn to pieces Chapman proclaims that ‘Holland Fen shall never be enclosed or divided’ and the crowd disperse singing ‘Thus the Act has fallen, has fallen, has fallen / Thus the Act has fallen to rise no more!!’ The Stranger, it appears, has been able to act as a reagent, enticing William Smith to act as an agent provocateur and to stir rebellion – but for what end?

The second act begins with the forces of authority now staking their positions. The landowner, John Yerburgh, is adamant that the mob must be faced down; whilst Fydell, a Justice of the Peace, hopes that passions will subside before there is any need for action to be taken. But when a game of football is played on the fen, an action which has precipitated riots elsewhere, the local MP Sir John Cust suggests that examples need to be made of the ringleaders, even if men are to be hanged.

It is time for The Stranger to appear again. The Bankers who took over the meat stall are now being refused a drink in a public house because they cannot pay. They protest that this is because they can’t work the navigation because of the rioters. Urged on by The Stranger, and not withstanding arguments within their ranks, they start to smash up the inn and to burn it down; for which they are arrested. Once again the violence that is taking place has been stirred up by the outsider.

Yerburgh the landowner now offers the Bankers freedom if they will help capture the ringleaders of the mob, which they agree to do; but when they confront the slodgers, who have now armed themselves, they back down. The situation escalates. Charles Pelham has told all of his tenants that they must go to Boston to declare their support for Enclosure or they will be thrown off of the lands. The slodgers are recruiting more men and gathering more weapons. The Reverend Calthorp is adamant of the need to ‘Transport the blackguards – give every man jack of them a taste of the whip – we need the army’. Two hundred soldiers are sent to the town to confront the six hundred rioters who are extorting ‘money, meat and drink from the inhabitants of towns in the Fens’, as well as acquiring two hundred guns and other arms.

The night before the army arrives Robert Chapman, the radical, is given a letter in which it is stated that he should head to London because that is where the main work for the revolution must be done and that William Smith is to become the leader of the local action as ‘Loinham doesn’t know what to do next. Smith must take command and begin the revolution here’. Before the letter is passed on to Smith, The Stranger confronts him once again. ‘Who are you? Where do you come from?’ Smith asks, receiving no reply to his question, only the orders that as the soldiers on their way it is imperative that ‘the rioters must act now’. Smith replies that he has done enough already for the money he has been promised; but the Stranger insists that he stir the mob into action before he ‘MOVES OFF QUICKLY INTO THE SHADOWS’.

Chapman enters and gives Smith the letter that states that ‘This Act concerning the closing of Holland Fen is one of the most tyrannic and oppressive ever was made in the British Nation since the Norman Conquest’. Smith is aware that the letter, through asking him to seize arms and form an army, is a seditious act punishable by death and rushes off to show it to the magistrates and to try and save himself.

Smith hands the letter to Fydell, a Justice of the Peace, telling him that he received it from Robert Chapman. Smith is escorted off as ‘STEPPING OUT OF THE SHADOWS IS THE STRANGER’. Smith is brought before the authority figures – Fydell, Calthorp and Cust – and as he reveals the names of the ringleaders the men are pulled out of the crowd. THE STRANGER appears again:

SMITH: I need that money, and I need your word to the magistrates.

STRANGER: I don’t deal with magistrates.

SMITH: You work for them.

STRANGER: I am a stranger in these parts, friend – I merely pass through.

This is the final time that we see The Stranger as the play now moves towards its climactic ending. Yerburgh, the landowner, tells the crowd that ‘Today the Enclosure Commissioners meet for the last time’ and that with the ‘rabble’ having been arrested ‘Within a month the first fences will be put up’. The trial of the men whom Smith has given up is to take place, but ‘FROM THE SHADOWS SOME OF THE CROWD EMERGE WITH SCYTHES’ and the ‘RINGLEADERS ARE FREED OF THEIR CHAINS’. Smith appears to be a changed man, exhorting the crowd to continue the fight as Norris Loynham declares ‘We’m beaten. Oh yes, we can knock their fences down, but they’ll only build them again’. In a rousing finale the cast sing ‘But the gentry must come down / Stand up now, stand up, stand up now / And the poor shall wear the crown’ as William Smith is given the final words of the play – ‘There will be no surrender’.

So who was The Stranger, the outside force who seems able to stir the blood, to quicken the action, and to bring the combustive elements that exist within the community together so that there is both a riot and also the capture of the ringleaders of this riot (even if they are released at the end by the crowd)? Is this character an agent of the State, helping to bring simmering feelings of discontent to the surface so that the opposition can be violently crushed by the soldiers (which for most of the play he appears to be)? Or is he some kind of revolutionary, genuinely hoping to stir revolt within this community before stirring up similar action elsewhere?

Perhaps it does not matter. Perhaps what is more important is the fact that The Stranger seems to personify the outside forces that are bearing down on the community; outside forces which will reshape shape the community through convulsive acts that are inherently bound to cause conflict. The Stranger is a character that cannot be understood, someone who appears to come from nowhere, just as the forces that are confronting the community cannot be clearly understood. In this play these forces are seen as destructive, as reshaping the landscape from a common ownership (of sorts) to a more private one, with all the ramifications that are to follow. The Stranger is the destroyer of community. Even if the community has its own forces within it that are ready to tear it apart, it has taken this figure to bring them into play.